The Artist in Nature

The months spent staying indoors and working from home have made many of us long for the outdoors and a closer contact with nature, be it in our own back garden, the nearest park, or in the green spaces of our imagination. As the proliferation of exhibitions and cultural initiatives devoted to nature, botanical art and the pleasure of gardening attests, never before has the importance of preserving and enjoying nature felt more pressing than in the current global climate (just last week, I attended a webinar devoted to the practice of drawing weeds, learning more on the art history of weeds while also trying my hand at some observational drawing!) It will thus come as no surprise that I have turned to a group of depictions of artists working outside in search of some respite. As a disparate group, the four drawings briefly discussed here, exemplify the multi-faceted nature of the relationship between draughtsman and landscape and the enduring appeal of the motif of the artist at work out of doors.

When I think of the thrill of painting en plein air, I am immediately reminded of the witty and light-hearted drawings of Henri-Joseph Harpignies (1819-1916). While readers may be familiar with Harpignies as a landscape painter, in the collection he appears as the creator of many a delightful drawing featuring an artist perched on a tree branch or high on a hilltop with his paint-boxes precariously balanced at his side. These intimate monochrome sketches, datable to around 1900, have the spontaneity of an impromptu drawing and owe their appeal to their small scale. The figure of the artist is often little more than a few dabs of ink or chalk marks, as in the sheet with two be-hatted artists sharing a session of en plein air painting or drawing, aptly inscribed, INTREPIDITÉ (fig. 1).

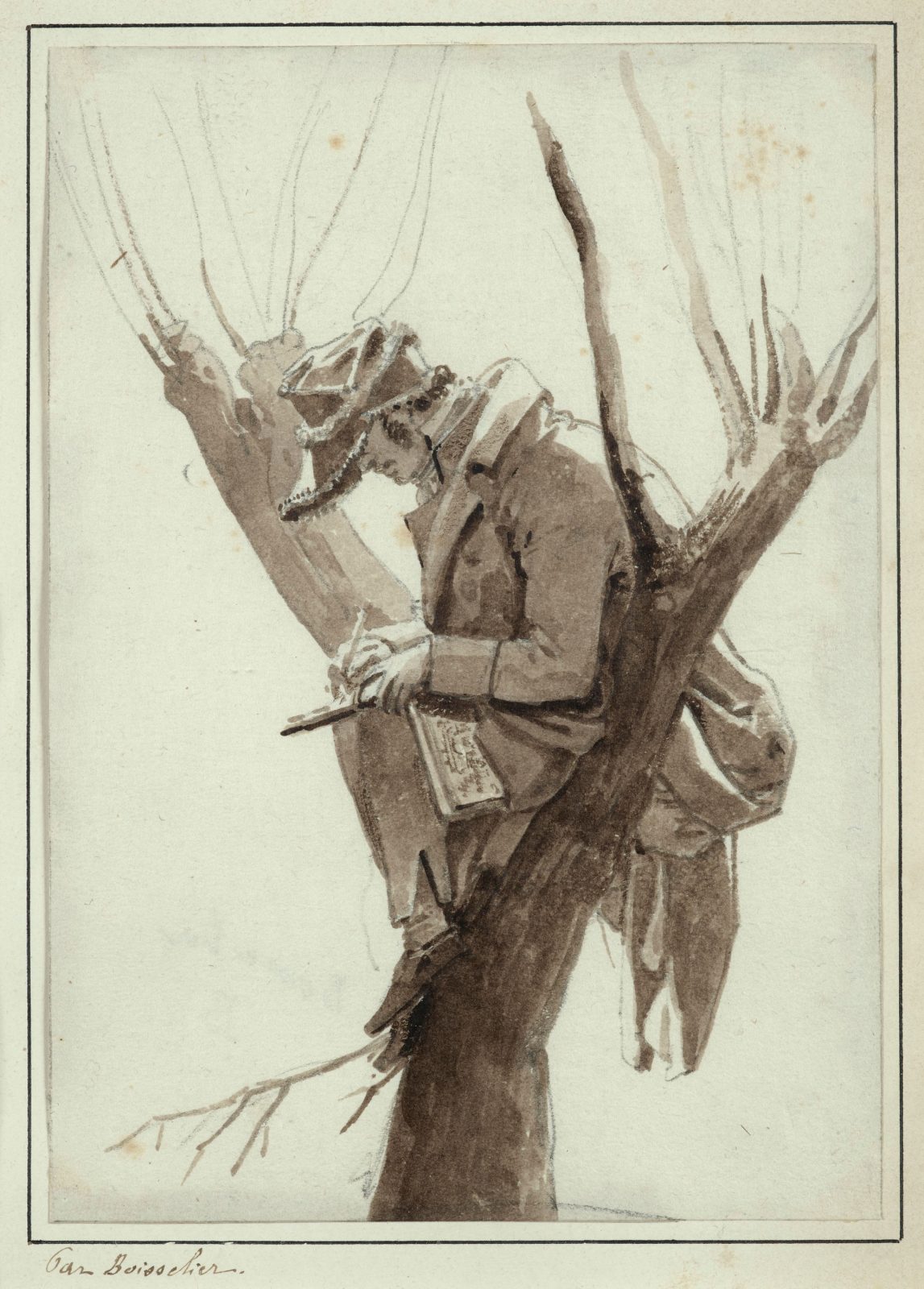

Another landscape painter who played with the motif of the intrepid artist in search of the perfect viewpoint is Antoine-Félix Boisselier (1790-1857) (fig. 2). Here, the artist in his peaked cap is perched in a tree with his sketchbook resting on his knees. While Boisselier devotes equal attention to the delineation of human figure and natural elements, and Harpignies delivers an atmospheric study of nature with the inclusion of artists at work, the next two examples differ in their focus.

The delicate watercolour by Johann Christian Reinhart (1761-1847), A Farm in Connewitz near Leipzig, is an early work and shows a concern for the overall scenery as well as its constituent parts (fig. 3). The figure of the draughtsman sitting on a patch of grass in the foreground hints at the central practice of working from life. Clearly separated by a line, the lower part of the sheet also includes other close studies, like that of a plantain accompanied by its botanical name, Plantago. It is this detailed study of a plant that inspired me to choose my fourth example, different in style and yet close in spirit.

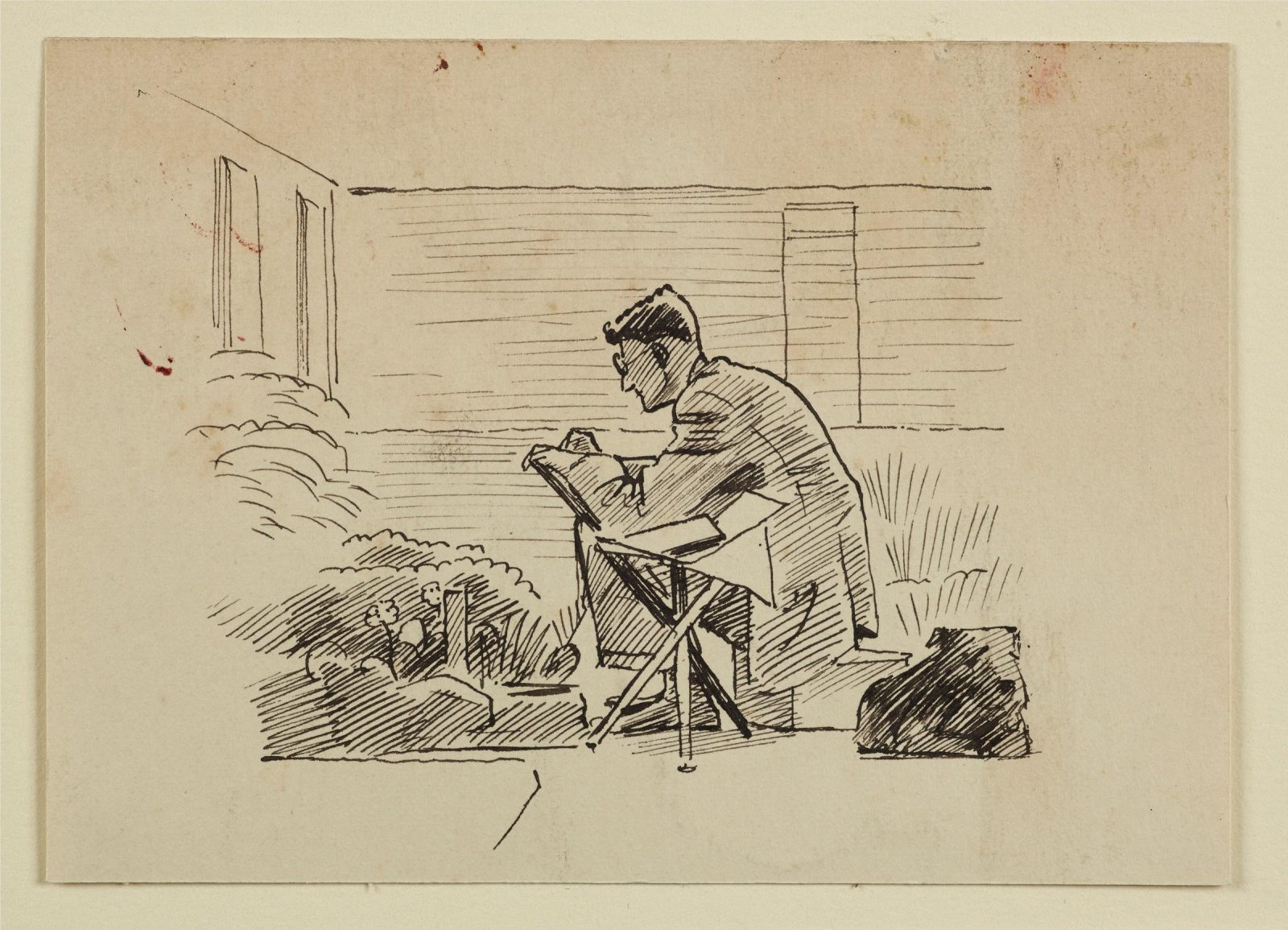

A pen and ink drawing by Evelyn Dunbar (1906-1960), Charles Mahoney sketching plants in the garden of The Cedars (fig. 4), reads as a personal record. Dunbar captures her then partner Mahoney in a moment of daily life and work at her family home in Strood, Rochester, in the company of the family dog, Paul. In 1936, both artists were busy preparing plant studies to illustrate Gardeners’ Choice (Routledge & Sons, 1937), which they also co-authored.

Mahoney had been Dunbar’s tutor at the Royal College of Art and later invited her to collaborate on a mural at a school in Brockley. Due to their mutual passion for plants and horticulture, soon after it would be Dunbar to invite Mahoney to share a commission for ‘a really new book’ about gardening. The novelty of Gardeners’ Choice is given by the freshness of the illustrations, which combine close studies of botanical specimens with lively vignettes, and by the choice of plants, selected with a preference for uncommon and overlooked species.

The book would be Dunbar and Mahoney’s final collaboration and their relationship would reach breaking point by its completion. Previously only known as a war-time artist — she was the sole woman artist to be salaried throughout WWII — Evelyn Dunbar was rediscovered in 2013 when her long-forgotten studio contents were retrieved by a relative in her attic in Kent. The unveiling of over 500 paintings, drawings and studies, including the present sheet, prompted a reconsideration of her importance in British twentieth-century art.

Explore related themes: En plein air; Women artists

Learn more about Evelyn Dunbar and Gardeners’ Choice here:

https://evelyn-dunbar.blogspot.com/2012/06/gardeners-choice-1937.html

Fig. 1 Henri-Joseph Harpignies (1819-1916), Two Draughstmen in a Landscape, 1894, pen and black ink, grey wash, 145 x 100 mm, Katrin Bellinger Collection, inv. no. 2012-012

Fig. 2 Antoine-Félix Boisselier (1790-1857), An Artist with a Sketchbook, perched in a Tree, pen and brown wash, black chalk and pencil, 150 x 107 mm, Katrin Bellinger Collection, inv. no. 1996-008

Fig. 3 Johann Christian Reinhart (1761-1847), A Farm in Connewitz near Leipzig, 1785-85, watercolour over pencil and ink, 285 x 330 mm, Katrin Bellinger Collection, inv. no. 2018-045

Fig. 4 Evelyn Dunbar (1906-1960), Charles Mahoney sketching Plants in the Garden of The Cedars, c. 1936, pen and ink, 85 x 120 mm, Katrin Bellinger Collection, inv. no. 2015-032