Reflections on Connecting Worlds: Artists and Travel, in Dresden

The world is a book and those who do not travel read only one page.

― St. Augustine

Nothing can be compared to the new life that the discovery of another country provides for a thoughtful person. Although I am still the same I believe to have changed to the bones.

― Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Italian Journey (1816–17)

The international loan exhibition Connecting Worlds: Artists & Travel realised by the Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden (SKD) in collaboration with the Katrin Bellinger Collection closed its doors on 8 October 2023. Hosted in the spacious galleries of the Dresden Residenzschloss the dynamic display of over 120 works, primarily drawings and prints, was conceived to take visitors on a journey across different historical periods and geographical contexts. It relied on the unique power of works on paper to bridge distances and enable new connections. From the Renaissance to the nineteenth-century, from Albrecht Dürer’s journeys to those of the young Nazarenes and beyond, the selected drawings, sketchbooks and prints revealed experiences made on the road, telling of personal aspirations, friendships and exchanges nourished by travel. We selected most of the works from the rich holdings of the SKD and combined them with a substantial group lent by the Katrin Bellinger Collection. In addition, thanks to the generosity of colleagues and lenders we were able to supplement our two collections with a number of remarkable loans from institutions in Germany, Switzerland and the UK.

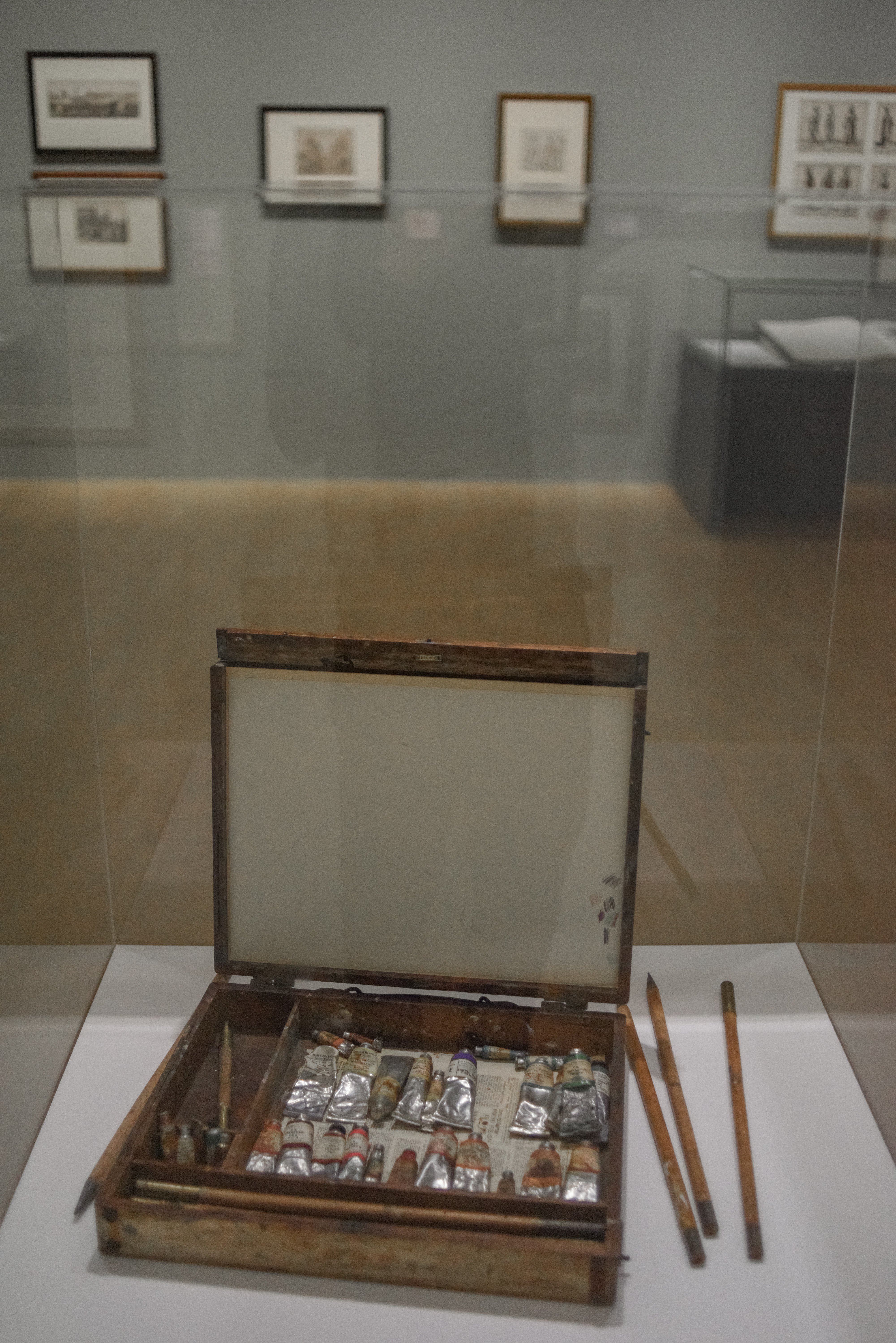

The loans from the Katrin Bellinger Collection included small sketches of artists at work en plein air such as Lambert Doomer’s atmospehric drawing of a behatted draughtsman seen from behind (fig. 1), as well as larger watercolours like Thomas Rowlandson’s Artist travelling in Wales, and artists’ tools. A well-used portable paintbox/easel (fig. 2) and a refined watercolourist’s walking cane were amongst the most popular exhibits with visitors. Similarly admired was Eugène Emmanuel Viollet-le-Duc’s masterful watercolour (fig. 3) showing the artist sketching the inside of a glacier while trapped in a crevasse – one of the tiniest self-portraits in the collection!

THE JOURNEY

While offering some insights into the exhibitions structure and key themes I wish here to mainly share my experience of working on the project for the past three years and reflect on this journey now that it has come to a close. I co-curated Connecting Worlds and co-edited the accompanying catalogue together with Stephanie Buck, Director of the Dresden Kupferstich-Kabinett. I first met and worked alongside Stephanie when she was Curator of Drawings at the Courtauld Gallery and it was a privilege to realize this exhibition with such an imaginative and forward-looking curator and champion of works on paper.

The project was only possible because we enjoyed Katrin Bellinger’s unwavering support and enthusiasm in seeing it realized. She encouraged our ambitious scope and the creative directions we pursued in wanting to recreate for our visitors the spatial and intellectual experience of being ‘on a journey’. This also entailed enlisting the collaboration of other essential members of our team, alongside the brilliant colleagues at the SKD, starting with Mark McDonald, curator at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, who generously acted as curatorial advisor and was instrumental in helping us define the key role of prints as agents of change and exchange within the display.

Early in the project we realized that an exhibition focusing on travel could not unfold according to a prescribed path but would necessarily be open to individual discovery with each visit allowing for a new route and new connections to be made. This is exemplified by the role played by Pieter Coecke van Aelst’s Costumes and Manners of the Turks (1553). One of the most influential printed depictions of a journey, it is a series of ten woodcuts relating to the Flemish artist’s travels to Constantinople. We invited London-based artist duo Ben Langlands and Nikki Bell to imagine a new way of exhibiting these detail-rich prints. I had the pleasure of working with them on the exhibition Absent Artists, which they curated at Charleston in 2022, and was keen for our collaboration to continue. Having understood the crucial role that travel plays in their work and thinking I was delighted when they agreed to lend their 1999 neon sculpture Frozen Sky as well as contribute to the exhibition design. Their vision of a set of curved vitrines that would require visitors to consciously move in the space was to inform our use of the galleries more broadly (fig. 4).

The balance of dynamism and elegance in the display was in large part due to the contribution of the artist and designer Ines Beyer, whose thoughtful approach gave life to truly poetic passages. One of my favourite features was the tall vitrine where we displayed several sketchbooks, some open and some closed, to illustrate their material qualities as well as their functions (fig. 5).

The sketchbook as a portable and flexible tool was at the heart of the first section of the show, ‘On the Road’, focusing on the artist as traveller and the practice of working outdoors. This was followed by ‘Destination Rome’ which centred on the Eternal City as a dream destination for travellers, tourists and artists from the Renaissance to the 19th century. A different type of travel – travel of the mind – was highlighted in the third section, ‘Dresden’, which looked at the sumptuous collections assembled by the Electors of Saxony from the perspective of their interest and curiosity about the cultures of Turkey, India, China and Brazil as expressed in a variety of artifacts and images (fig. 6).

TRAVEL AND FRIENDSHIP

Collaboration and sharing of expertise are at the heart of many successful exhibitions but in the case of Connecting Worlds their importance took on further meaning. Ever since we started brainstorming on the core themes for the show one emerged strongly for me: friendship. Companionship – or the longing for it – marks many artists’ experiences of leaving their home and pursuing new adventures.

Whether artists travelled in groups, like Johann Anton Ramboux and the Eberhard brothers, or encountered new friends at their destination, like Goethe and Angelica Kauffman who met in Rome, drawings often served to celebrate a bond. Portraits has a particular role to play. Some appear to have been spur of the moment, like Ernst Fries’ likeness of a young Camille Corot in a moment of contemplation in Cività Castellana, outside Rome (fig. 7). Others are formal commemorations, like Johann Georg Schütz’s spectacular watercolour depicting the entourage of Duchess Anna Amalia of Saxe-Weimar-Eisenach in the gardens of Villa d’Este in Tivoli, lent by the Klassik Stiftung Weimar (fig. 8).

Friendship and memory come together in several of the sheet, especially in the section devoted to Rome as the meeting point for an international milieu of artists, patrons, Grand Tourists. For example, in the large sheet by Johann Anton Ramboux at the Städel Museum, Frankfurt am Main (fig. 9), I found a ‘concealed’ self-portrait / group portrait. The main subject of the watercolour is the Feast of the Infiorata in the town of Genzano, outside Rome, but amongst the crowd of local onlookers, in the middle ground on the very left, we spot four Northern artists. With his peaked cap, satchel and sketchbook under his arm, Ramboux himself turns to gaze at the beholder. It was the presence of the artist, arguably motivated by the desire to crystallize the memory of that day, that called for the inclusion of this little-know and beautifully preserved sheet in the exhibition.

NEW PERSPECTIVES

As well as prompting new research, the project of Connecting Worlds inspired me to consider the types of questions we want to ask about the ‘Artist at Work’ collection. For example, what do we know about the experience of travelling as a woman and how is it reflected in specific works? The exhibition included famous women artists, such as the pioneering naturalist Maria Sibylla Merian (1647–1717), who travelled from Amsterdam to Surinam in 1699 (fig. 10), and the cosmopolitan neoclassical painter Angelica Kauffman (1741–1807). But we also told the stories of less well-known early travellers, like the intrepid landscapist Louise Joséphine Sarazin de Belmont (1790–1870) who sought out the remote sceneries of the Pyrenees and was later captivated by the majesty of ancient Rome.

Moving forward we will continue to pursue thematic exhibition that may yield fresh insights into our holdings. Connecting Worlds has also strengthened our belief in the virtues of a transhistorical approach. With works that now span from the 14th century to today the potential for new connections is limitless. It was inspiring to see how in Dresden interventions by contemporary artists brought the dialogue between travel and image-making into the present, opening to new approaches to the historic pieces.

Although the exhibition is now closed, I am pleased to see that several forthcoming initiatives will further investigate the relationship between travelling and drawing. In March 2024, in particular, I look forward to continuing the conversation at the conference ‘Landscape drawing in the making: materiality – practice – experience, 1500–1800’ at the Fondazione Cini in Venice and at the study days hosted by the Salon du dessin in Paris on the theme of ‘Travel drawings’.

For those who missed Connecting Worlds: Artists & Travel or wish to revisit it, a virtual tour is available through the SKD’s website, and the richly illustrated exhibition catalogue offers boundless trails to pursue and be inspired by. As well as carefully researched catalogue entries it features essays by an international panel of experts addressing such topics as the uses of artist sketchbooks across time, encounters with the Ottoman world, travel as a topic for prints, travel and collecting at the Saxon court.

Exhibition catalogue

Stephanie Buck and Anita V. Sganzerla, eds., with the assistance of Jane Boddy, Connecting Worlds: Artists & Travel, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, Kupferstich-Kabinett, in association with Paul Holberton Publishing, 2023. Find it here

Fig. 1 Lambert Doomer, An artist seated by a tree, sketching, early 1660s, Katrin Bellinger Collection (cat. 18.1)

Fig. 2 Installation view. Photo: Chris Boulden

Fig. 3 Eugène Emmanuel Viollet-le-Duc, The artist sketching while trapped in a crevasse, 1870 (cat. 23)

Fig. 4 Installation view. Photo: Courtesy Langlands & Bell

Fig. 5 Installation view. Photo: Chris Boulden

Fig. 6 Installation view of 'Dresden' room with Frozen Sky (1999) by Langlands & Bell. Photo: Courtesy Langlands & Bell

Fig. 7 Ernst Fries, Camille Corot in Cività Castellana, 1826, Kupferstich-Kabinett, SKD, inv. C 1963-835. Photo: Herbert Boswank (cat. 55.1)

Fig. 8 Johann Georg Schütz, Duchess Anna Amalia of Saxe-Weimar-Eisenach with her entourage in the gardens of Villa d’Este, Tivoli, 1789, Klassik Stiftung Weimar, Graphische Sammlungen, inv. KHz/02075. Photo: Susanne Marschall (cat. 49)

Fig. 9 Johann Anton Ramboux, The feast of the Infiorata, Genzano, 1821, Städel Museum, Frankfurt am Main, inv. 5691 Z (cat. 44)

Fig. 10 Jacobus Houbraken after Georg Gsell, Portrait of Maria Sibylla Merian, c. 1717, Kupferstich-Kabinett, SKD, inv. A 36998